Origins: Game & Fish Commission

The first coastal area management conducted by the state of Georgia was through the appointment of a Tidewater Commissioner in 1924 within the Game and Fish Commission, an early predecessor to the modern Wildlife Resources Division. The Tidewater Commissioner was only in place until 1931, and it was not until 1940, when Charlie Elliott, director of the Wildlife Division within the 1937 iteration of the DNR, wrote an article for Outdoor Georgia about the need to support the expansion of seafood production and saltwater fishing, that coastal resource management began to take hold in Georgia. In 1943, the Department of Natural Resources was dissolved and the Game and Fish Commission was created. As its first commissioner, Elliott appointed Joe Mitchell, formerly the director of the Wildlife Division, as supervisor of the newly formed Coastal Fisheries Office.

Early History: The Coastal Fisheries Office

During its early years, the Coastal Fisheries Office's mission was to manage the commercial fishing industry. The shrimp industry was, and has remained, one of the state's most important commercial fishing businesses, and was an early focus for the office's management of coastal waters. Oysters were also a concern during the early years, as oysters were being harvested out of polluted waters and then sold for consumption. In 1948, the Coastal Fisheries Office, headquartered in Savannah and Brunswick, represented about 8 percent of the Game and Fish budget, comparable to the 7 percent allocated to the fish hatcheries.

The Dingell-Johnson Act, also known as the Sport Fish Restoration Act of 1950, was a pivotal piece of legislation for the country as a whole, and fueled Georgia's own fisheries management programs by providing considerable funding for the support of fisheries management. The Dingell-Johnson Act authorized the Secretary of the Interior to provide financial assistance for state fish restoration and management plans and projects. With the help of this extra funding, during the 1950s and 1960s, the Coastal Fisheries Office concentrated its efforts on sport fish restocking and fishing licensing. Much of this early work was overseen by Coastal Fisheries Office supervisor David Gould, who had a long career with DNR beginning in 1950. After his retirement in 1980, Gould became Executive Director of the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council.

A 1964 state review was conducted of the Game and Fish Commission, calling for more support of the Marine Fishery program. Specifically, the review pointed to the need for a qualified laboratory staff and modern equipment, improved law enforcement, a modern marine laboratory, and a marine fisheries resources rehabilitation program. "As part of the over-all game and fish long-range planning program, special emphasis should be given to the marine fisheries resource needs as a prelude to the acquisition of lands and facilities to assure an orderly, planned development program to overcome the effects of long years of neglect:' This review signaled a growing urgency to properly address coastal resources management, a concern that led to pivotal legislation, the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act.

Evolution: The Coastal Marshlands Protection Act

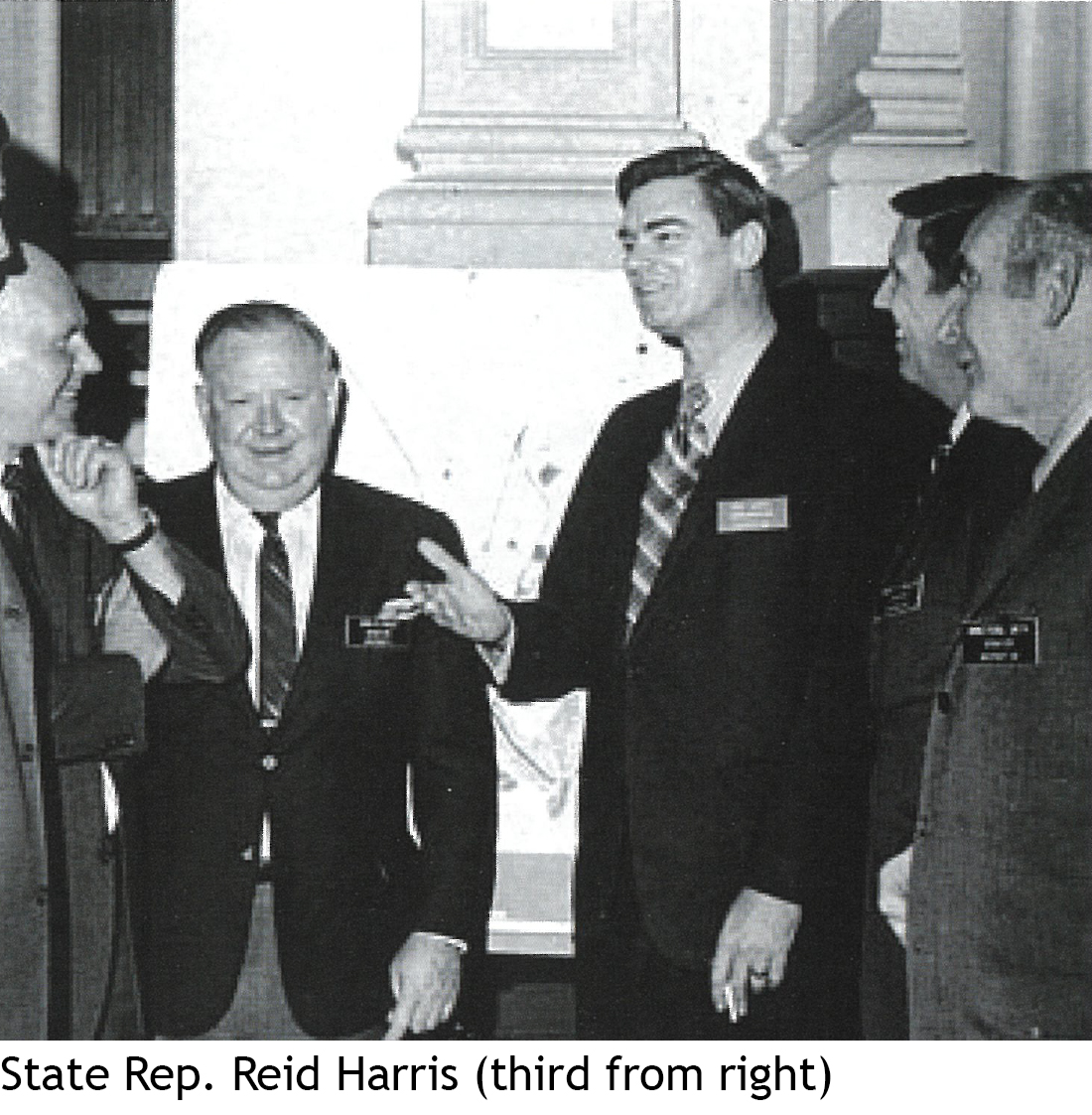

The passage of the 1970 Coastal Marshlands Protection Act is one of the most significant legislative acts in Georgia's environmental record, and defines much of the history of the Coastal Resources Division (CRD). The act was born out of the State Water Quality Control Board's fight against a powerful corporation seeking to mine along the coast. The Kerr-McGee Corporation applied for a permit to mine phosphate in 1968, following two years of exploration along the Georgia coast. The application raised an alarm for those in the state who knew of the ecological importance of Georgia's marshes. This attention to the coast was due in part to Dr. Eugene Odum, a UGA biologist, and his brother Howard T. Odum, an ecologist. The Odums brought attention to the importance of the state's marshland ecosystem through their work at the UGA Marine Institute at Sapelo Island. Reid Harris, a state senator, wrote the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act in 1969, a year after he and Rock Howard of the Water Quality Control Board (predecessor to the Environmental Protection Division) ensured the passage of the Surface Mining Land Use Act, which placed controls on the manner in which mines were abandoned after the ore had been extracted. Harris saw that the push from a big industrial company like Kerr-McGee would not be contained by the Surface Mining Land Use Act alone, and knew that a mining operation of that scope would be devastating to the coast.

In 1970, the Coastal Marshland Protection Act was signed by Governor Lester Maddox, with advocates for the coast, including the influential Jane Hurt Yarn, petitioning the governor for the bill's passage. Not everyone at the time held a favorable view of the bill, especially developers with an interest in building along the coast. The law, and the oversight of construction permitting along the coast provided by the modern CRD, have had a lasting impact on the conservation of Georgia's coast. Significantly, the majority of the state's barrier islands are under state or federal ownership and approximately 70 percent of Georgia's maritime forests have been preserved. The current CRD director, Doug Haymans, and his predecessors Spud Woodward, Susan Shipman and Duane Harris, are proud of the legacy of the Act and the CRD's efforts in ensuring the Act's measures are carried out. For, Woodward once remarked, the coast "looks pretty much the way it did when we started; and there aren't many states that can make a similar claim.”

The Creation of CRD

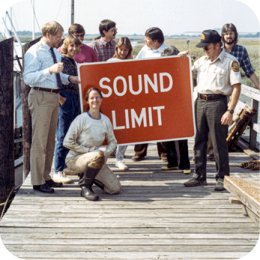

When the DNR was created in 1972, the Marine (also called Coastal) Fisheries Office remained under the Game and Fish Division. That same year, President Richard Nixon signed the Coastal Zone Management Act (CZM), encouraging states to work with their local governments and with the federal government to develop unified land and water use programs. In 1978, Governor George Busbee signed the Georgia Coastal Zone Management Act, and established an 18-member Coastal Zone Management Board to approve Coastal Zone Management grant applications, develop policies, and recommend guidelines for the wise management of coastal resources. The Georgia Coastal Management Act, coupled with the passage of the Coastal Marshlands Protection Act in 1970, signaled an official dedication to managing the state's coastal resources. The state's coastal interests, bookended by these two landmark legislative acts, led to the establishment of the Coastal Resources Division (CRD) in 1978.

Dr. Robert Reimold served as the division's first director, overseeing the review of coastal construction applications, the management of commercially harvested seafood, and working with the Environmental Protection Division to ensure that the coastal waters were protected from pollution by restricting certain areas from fishing. This work continued under Bob Mahood who served as CRD's director from 1980 to 1983, and under Duane Harris, the division's first of three long-term division directors. A career DNR employee, Harris began working for the Office of Coastal Fisheries in 1970 while it was still housed under the Game and Fish Commission. Harris discovered the North Atlantic Right Whale calving grounds in 1979 while working as Chief of Fisheries. Because of his efforts to call in a DNR filming crew that had just left the area, the mother whale and calf were filmed seven miles offshore. The recording of this significant moment proved important for the future study of the sea mammals, whose calving grounds remained unknown until that point.

CRD's commitment to coastal wildlife can also be seen through its efforts to protect sea turtle populations. Georgia was the first state to provide turtle excluder devices (TED) to shrimpers. TEDs are designed to prevent sea turtles from becoming trapped in the shrimpers' net. The devices became mandatory throughout the United States in 1987 and have been an important component of protecting sea turtles. Indeed, sea turtle populations, through the efforts of CRD and WRD, have enjoyed a resurgence in numbers. In 2015, over 2,300 nests were identified, up from an average of 1,000 nests in the early years of conservation.

In 1989, under Harris' direction, the division moved to the newly built Coastal Regional Headquarters in Brunswick, a regional DNR office, that houses not only CRD staff, but WRD (game and nongame programs), LED, and Parks and Historic Sites staff who work with coastal resources. The interdivision collaboration that is unique to coastal resources has been an important part of CRD's history, particularly when Georgia joined the federal Coastal Zone Management Program, a program where DNR's divisions all participate to some degree. Georgia joined the program in 1992. CRD developed a management plan tailored specifically to the state, one that provided better guidance for Georgia than the national CZM plan. After Georgia became part of the federal CZM program, the state was able to receive federal funds in the form of Coastal Incentive Grants (CIG), a grant program funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The CIG Program has been an important resource to the state's communities and universities, providing funding for important programs such as CRD's popular CoastFest, held annually since 1995 and drawing thousands of visitors to the coastal area.

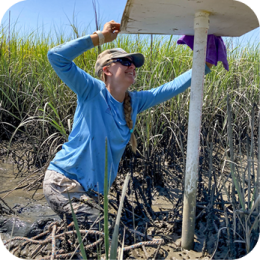

With an educational background in marine and bird zoology, Susan Shipman became the CRD director in 2002. Shipman began at CRD in 1983 and worked as a research biologist and the Chief of Fisheries prior to becoming director. She oversaw the continuation of regulations for the fishing community to promote a sustainable future for the commercial fishing industry. Under her leadership, CRD continued efforts with the artificial reef program, which started in 1970 to develop long term fisheries habitats. These include inshore and offshore artificial reefs, which promote recreational fishing in the state. CRD has used sunken vessels, concrete culverts, battle tanks, and even old subway cars to create these habitats.

Following Shipman's tenure, Spud Woodward served as director from 2009 to 2017. Under his leadership, CRD's responsibilities grew to include several programs that promote the appreciation of coastal resources and ways to keep them sustainable, including events like CoastFest and Beach Week. CRD remains a strong voice for Georgia in regional organizations like the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council and Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission.

CRD Today: A Focus on Sustainability

In 2017, after 17 years in various CRD roles, the sixth and current director, Doug Haymans, began what has been a particularly interesting period for CRD. Back-to-back-to-back hurricanes (Mathew, Irma, Michael), the roll-over of the roll-on-roll-off M/V Golden Ray in St Simons Sounds with its ensuing 2-and-a-half year clean-up, COVID-19, and $9.2M in aid to the fishing community ushered in a truly unique time. Despite these ‘distractions’ CRD continues its 40-year commitment to implementing fare and enforceable fishery management policy, assisting coastal property owners with Marsh and Shore permits and revocable licenses and developing the burgeoning shellfish industry, through thoughtful legislation and rulemaking. Examples of the latter include much needed attention to residential docks and bank stabilization rules, live-aboards and abandoned vessels.

Although many challenges lie ahead, CRD will continue to uphold the protective laws that have made the Georgia coast sustainable. The coast has maintained its integrity because of the hard work and laws that were passed decades ago, but the pressure for coastal area development continues. It is easy to take for granted that the coast will look as it does forever, but in reality the hard work continues for more than 65 dedicated CRD employees.

Adapted from "An Enduring Reverence: Georgia's Department of Natural Resources" (2015). Updated February 2024.