Posted Sep. 8, 2025

Coastlines Georgia | August 2025 | Vol. 8, Iss. 1

.jpg)

The living shoreline at Cannon’s Point Preserve on St. Simons

Island is seen in an unmanned aerial vehicle photo

taken Oct. 18, 2022

By Tyler Jones

Public Information Officer

Georgia’s coast is losing ground to rising seas and stronger storms, and property owners want protection that won’t sacrifice the habitats that make this place special.

To help, Coastal Resources Division, working with an experienced coastal engineer and contractor, has released “Living Shorelines in Coastal Georgia: A Comprehensive Guide to Understanding and Designing Living Shorelines on the Georgia Coast.”

The guide turns science into practical steps for deciding where living shorelines make sense, how to design them, and how to build them to last.

A living shoreline uses natural materials—marsh grasses, oyster shell, coir fiber, and sometimes low rock—arranged to slow waves, trap sediment, and let marsh migrate. It’s a different philosophy than building a wall.

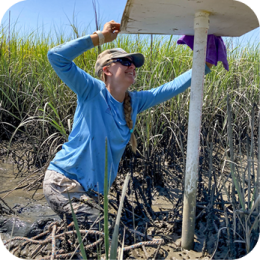

As CRD wetlands biologist Meghan Chrisp puts it, “Living shorelines are engineering with nature. We look at what already works in the marsh and design a project that strengthens those natural processes.”

The guide focuses on three essentials: site suitability (fetch, wakes, currents, adjacent features); design standards (gentle bank slopes, planting elevations, compatible materials); and best management practices (oyster recruitment, upland stormwater controls, and native vegetation). It also offers case studies, plan examples, cost comparisons with hardened structures, an FAQ, and resources.

Chrisp cautions that walls aren’t always the best first option.

“Bulkheads and similar structures can be appropriate in some situations,” she said. “But they can also trigger ‘flanking’—erosion that digs out the edges of the wall over time—and that can undermine the very protection people are paying for.”

By contrast, living shorelines dampen waves, encourage sediment to settle, and keep marsh-to-upland connections intact.

“That connectivity matters,” Chrisp said. “A living shoreline lets terrapins, fish, crabs, and birds use the habitat they depend on while still protecting your property.”

Oysters are a frequent star. Placing shell or other substrate invites larvae to settle and build a self-repairing breakwater. “Oysters are homebodies,” Chrisp said. “Once they attach, they grow into a reef that knocks down wave energy and creates habitat.”

Cost is another advantage. Concrete bulkheads often run $800–$1,200 per linear foot with heavy maintenance and lifespans under 30 years; many living shoreline designs come in around $500 per foot and recover naturally after storms.

Nearly a dozen have been built in Georgia since 2010. To expand capacity, CRD and partners hosted an Aug. 6, 2025 training in Brunswick for 14 engineers and contractors, growing the practitioner network to 34.

What should property owners know? Living shorelines aren’t one-size-fits-all; site visits and simple measurements matter. Success hinges on good design, appropriate materials, and early coordination with regulators. “Start the conversation before you start the project,” Chrisp said. “With the right site and design, a living shoreline can protect your bank, improve water quality, and add habitat—all at once.”

Learn more and download the guide at CoastalGaDNR.org/LivingShorelines.