Posted December 1st, 2025

Coastlines Georgia | December 2025 | Vol. 8, Iss. 3

Marine biologist combines love for science and passion for art with gyotaku

Tyler Jones

Public Information Officer

On a breezy weekday afternoon in Brunswick, long after the nets from the morning’s trawl have been hung to dry, marine biologist Britany Hall stands in her kitchen—the same place where most people might prep dinner or pack a lunch—and lays a flounder gently across a sheet of Styrofoam.

Her countertops are broad and spotless, which she jokingly calls her “Thanksgiving kitchen” because of how much room it offers. It has become her studio, her lab, and her quiet place to think.

She pins the fins carefully—“that part’s time-consuming,” she says—and with the same precision she brings to her work on the water, she begins brushing the fish with inky black pigment. Horsehair brush. Sumi ink from a hobby store. Each stroke soft, deliberate.

She leans in. Dab, dab—sponge to scale—to lift the excess and leave only what should be transferred.

When she’s satisfied, she drapes a piece of muslin cloth over the fish (a 23 inch flounder), smoothing it gently from head to tail. She pauses, palms flat, and then lifts.

A perfect imprint appears: the curve of the jaw, the rise of the dorsal fin, the faint dapple of pigment where the scales divide. A ghost of the fish, but truer in some ways than a photograph.

Hall smiles.

“You never know the reveal until you peel it back,” she says. “It’s either good, or it’s not, and you start over. Every print is different—no print is ever the same.”

This is gyotaku, an old Japanese technique for documenting fish catches. For Hall, it has nothing to do with bragging rights or record-keeping. It’s something else entirely—a bridge between the science she practices for a living and the art she creates simply because it brings her joy.

A Childhood on the Water

Hall grew up far from Georgia’s marshes—Gainesville, up around Lake Lanier—but water shaped her long before she ever studied fisheries or set foot on a research boat.

“I grew up on the water—that was just in my life,” she says. “My grandpa was my best friend, my Papa. He taught me everything about the outdoors.”

He lived right across the street. Fishing poles were never far from reach.

“I always tell everybody I’ve been fishing since I could walk,” she says, laughing. “And I’ve got the picture to prove it—little hat, little glasses, little fishing pole.”

That childhood—the lake, the quiet mornings, the time spent with someone who saw the natural world not as something to observe but something to share—set the foundation for everything that came later.

Finding Her Way to CRD

Hall didn’t plan on gyotaku. And she didn’t exactly plan on becoming a marine biologist, either—not at first. But one step led to another.

She majored in Environmental Science at the College of Coastal Georgia in Brunswick, then took on part-time work with CRD marine biologist Donna McDowell on the longline survey.

“I was her 29-hour a week employee on the longline survey,” she says. “Then I graduated, went off to do my master’s at Iowa State.”

Iowa, she admits, was an unexpected detour—cornfields instead of coastlines—but it’s where she first tried fish printing. The lab there had a huge freshwater buffalo and a carp mounted on the wall. She made a couple of prints for fun. Nothing serious. Not yet.

When she returned to Georgia, she saw an opening at CRD.

“I applied, and the rest is history,” she says.

Today Hall is part of the Ecological Monitoring Trawl Survey, the backbone of Georgia’s long-term fisheries data. The work is challenging—physically, mentally, sometimes emotionally.

“The hardest part is the time away,” she says. “It takes a big mental toll.”

But the rewarding parts outweigh it many times over.

“Every day we go out on the water, you have the opportunity to see something new,” she says. “And we’ve got a really great team. I wouldn’t want to work with anybody else.”

Bad weather? Engine trouble? Uncertain conditions?

She lights up.

“I work well under pressure,” she says. “Any kind of emergency situation—I actually thrive in that. I love the hard stuff.”

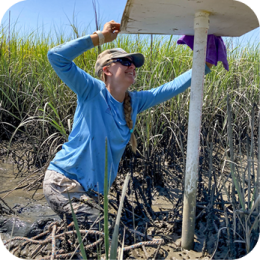

Marine biologist Britany Hall, right, helps public affairs assistant Fisher Medders make a gyotaku print on muslin cloth.

An Artist Hiding in a Scientist’s Job

Hall’s interest in gyotaku first saw piqued when she saw it online: social-media influencers pressing tropical fish onto rice paper. Later she saw prints again in professors’ offices in Iowa. Then pottery—her longtime side hobby—pulled her closer.

“I do pottery on the side,” she explains. “And part of that is I do transfers. It reminded me of the fish printing.”

A couple freshwater prints in Iowa. A carp. A big buffalo fish. Then, after moving back to Georgia, the idea resurfaced.

“It came back up on social media,” she says. “And I thought, I’m going to try that with a flounder.”

Before the flounder, though, came a cutlassfish she caught. Long, chrome-bright, almost metallic.

She printed that one first.

Then, one day, she printed her first saltwater flounder in Georgia.

“It’s a fun little hobby,” she says, but her tone—and her meticulous printwork—hint it might be more than that.

How a Print Comes to Life

Hall walks through the process like she’s teaching a class, which she very well might someday.

Step One: Clean the fish.

“You’ve got to get all the goo and slime off,” she says. “Make sure it’s really dry.”

Step Two: Work quickly.

“There’s a limited time,” she explains. As fish relax on ice, fluids seep out. “You need to be quick.”

Step Three: Prepare the fins.

Spread, pin, arrange. “If you want all the details of the fin rays, that’s pretty time-consuming.”

Step Four: Ink.

She uses sumi ink—“really potent”—either straight or diluted like watercolor. Paint with a horsehair brush. Dab with a sponge.

Step Five: Transfer.

Muslin, not rice paper, is her preferred medium.

“I like muslin better,” she says. “You get more detail, and it’s easier to work with. Rice paper gets creases.”

Lay the cloth from the top of the body downward. Press with a dry sponge over delicate areas.

Step Six: Reveal.

“Then you pull it up and see how you like it.”

In an hour or two, she’ll get maybe three or four good prints out of fifteen tries.

But when one is perfect, it’s unmistakable.

What Science Brings to the Art

At first, Hall hesitated when asked whether her scientific background affects the way she approaches gyotaku.

Then she reconsidered.

“I guess I have more respect for the characteristics of a fish,” she says. “The details of what makes a fish a fish.”

Someone without a background in anatomy might see only shape. Hall sees structure: fin rays, gill plates, scale patterns, the rise and fall of the body line.

Does gyotaku make her see fish differently as a scientist?

She shakes her head.

“I haven’t thought of it on that deeper level,” she says. “For me, it’s more of an art form—turning what I love about my job into something I can hang on the wall.”

A Trend at CRD?

Gyotaku has become quietly contagious among her coworkers.

“They like it,” Hall says. “I’ve gotten them started on it. I think I’ve started a little trend.”

She grins.

“Sean Tarpley [a marine technician with CRD’s Marine Sportfish Population Health Survey] just did another one the other day.”

People have begun asking if she’ll sell her prints. Some want to hang them in homes or offices; others say she should try an arts-and-crafts fair.

“I haven’t advertised anything,” she says. “The few I did here, I gave away.”

She’s not rushing.

Bucket-List Fish and Backyard Surprises

There’s one species she dreams of printing—mahi.

“The first time I ever saw anything related to this art form was with mahi,” she says. “That’s my bucket-list fish. When I get to catch one, I’m going to do a print of it. I’m going to bring the stuff with me the first time I ever catch one.”

She laughs at the thought of hauling muslin and ink onto a boat offshore.

“You’re gonna need a bigger piece of muslin,” I told her during her interview.

“Yep,” she replied.

Her most unusual print, though, wasn’t offshore. It wasn’t even from a trawl, net, or an other CRD survey. It was from her backyard.

A few months ago, she and her fiancee, Benson, took his son fishing in the pond behind their house. He landed a bluegill.

Hall hesitated only for a moment.

“I did a print on a live fish,” she says.

No pins. No stiffening on ice. Just a little fish with its fins up, holding still long enough for her to work quickly. Paint, press, print, release.

“Washed it off in a bucket and released it back into the pond,” she says. “First time I ever did that.”

Respect for the Water

Out on the trawl survey, Hall sees a lot—beautiful species, rare catches, surprising finds. But she sees something else too:

Trash.

“We see so much trash,” she says. “It gets pulled up in the trawl, gets stuck in the chain or the bag.”

She doesn’t mince words.

“Try to keep the ecosystem clean. It’s the fishes’ home. You wouldn’t want someone coming into your home and trashing it.”

It’s a message she knows sounds cliché, but one that matters.

“It’s always going to be an important message,” she says.

What Comes Next

Hall doesn’t know exactly where gyotaku will take her, and she likes it that way.

Maybe someday she’ll lead a workshop. She’s already brainstormed how CRD might introduce the art form at CoastFest using silicone molds and washable paints so kids can try it without using real fish.

“It could be a fun activity,” she says. Though she adds, “We’ll see,” with a smile.

For now, she prints after work or on weekends—“anytime the opportunity presents itself”—building a quiet collection of flounder, cutlassfish, bluegill, and carp.

What she’s really building, though, is something harder to categorize: a practice, a ritual, a way of seeing.

Back in her kitchen, the prints dry in soft afternoon light. She lifts one, admiring the delicate lines.

“I love moments like this,” she says.

On the water, she studies fish to understand an ecosystem. Here, she studies them to honor their beauty.

And in both places, she is doing what she does best:

Looking closely.

Paying attention.

Leaving an impression long after the tide goes out.