By TYLER JONES

PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICER

COASTAL RESOURCES DIVISION

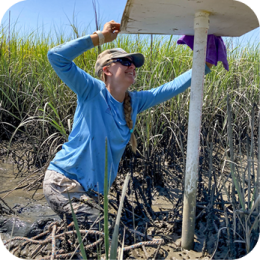

Ava Meier is not afraid to get her feet wet. Fresh out of college, she’s stepped foot-first into one of the dirties jobs at CRD, wading knee deep in muddy streams and stepping carefully along slippery rocks.

Meier and her fellow wetlands technician, Mariana Stonebreaker, are tackling one of CRD’s newest initiatives: The Aquatic Species Barrier Assessment.

“So far, we’ve been to more than 350 sites,” Meier said. “Each of the sites is some kind of barrier for aquatic species—so it’s culverts, bridges, anything where a road or a bridge intersects with a tidal water body.”

At each stop, the pair takes measurements and collects data about the potential barriers that could prevent aquatic species from crossing the structure. Information about the structure’s size is gathered, along with how much sediment is filling or obstructing the culvert or under the bridge, as well as the water’s salinity. Photos document the sites.

“We have to work fast,” Meier said. “Each day, we only get about four hours of workable time to get to as many sites as possible. The tide is the limiting factor, and we get about two hours on each side of the low tide for the day.”

The time constraints bring their own challenges. Because of the geology of Coastal Georgia, many of the sites Meier and Stonebreaker visit require them to wade through thick mud and shimmy down steep embankments. For safety, they wear long wader suits and high-visibility vests. They also have to keep an eye out for wildlife.

“We’re constantly looking for things like snakes and snapping turtles,” Meier said. “We also have to be mindful of bigger species like alligators.”

For as messy at the job may be, it’s an important one, said Jaynie Gaskin, a CRD wetlands biologist and Meier’s and Stonebreaker’s supervisor. Gaskin has been working with the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership (SARP) to evaluate the data collected on each barrier. SARP is a regional collaboration of natural resource and science agencies, conservation organizations and private interests developed to strengthen the management and conservation of aquatic resources in the southeastern United States. The results of this coastwide survey will be shared by SARP and CRD.

“SARP is what’s funding this project at CRD,” Gaskin said. “The overall goal of this is to develop an inventory of aquatic barriers for the coast and rank them based on how severely each barrier is limiting natural tidal flow. Based on this ranked inventory, we can target the worst aquatic barriers for replacement or remediation. Culverts and other restrictions present in tidal waters affect more than just wetland hydrology.

These aquatic barriers are affecting the life cycle of fish and other species that spend part of their life cycle in saltwater and other parts in freshwater. Our coastal estuarine wetlands act as a kind of ‘aquatic Kindergarten’ for a variety of rare species. This project will help us better understand how current aquatic barriers are impacting the connectivity health of Georgia’s wetlands, which is critical not only for species migration but also for hydrologic functions.”

Understanding how culverts and roads affect the ‘bigger picture’ of wetland hydrology is important as heavy rainfall associated with climate change is becoming more frequent, Gaskin said.

“It’s not uncommon now to have a heavy rainstorm that dumps two inches of rain in 30 minutes in some cases,” she said. “There’s also issues caused by increasingly higher high tides, and the hydrodynamics associated with more extreme tidal ranges. Having these data about how well these culverts and storm drains are functioning will help planners and biologists going forward to have a clear understanding of what’s happening in our wetlands.”

For each site, Meier and Stonebreaker also assign a numerical score based on the condition of the crossing. They’re looking to see how well the structure is functioning, and if it is appropriately sized for the amount of waterflow.

Once the project is complete, the data will also be shared with city and county planners to help them make decisions about public works and future culvert-crossing repairs, remediation, or even perhaps removal.

Knowledge of where there are trouble aquatic barriers can also help improve water quality and reduce flood risk. Simply being aware of a clogged or inadequate culvert can help planners know where to prioritize resources.

Another benefit comes from cleaner water and the reduction of pollutants. When aquatic species can move freely between different habitats, they can help to filter pollutants and control algae populations. They can also help to disperse seeds and other plant matter, which can help to improve the health of wetlands and other aquatic ecosystems.

Meier and Stonebreaker’s work is also helping to raise awareness of the importance of aquatic connectivity. Many people don’t realize that even small barriers can have a significant impact on the movement of aquatic species. By sharing their findings and experiences, Meier and Stonebreaker are gathering data that will help to educate the public about the importance of protecting and restoring aquatic connectivity.

Despite the challenges, Meier and Stonebreaker are passionate about their work. They know that their data is essential to protecting the future of Coastal Georgia’s aquatic ecosystems.

“There were some days back this summer that were unbelievably hot outside,” Meier said. “Still, it feels good to be able to help with this project and build a database that will help improve environmental conditions for all kinds of species.”

Gaskin said she expects the first part of the aquatic barriers project to be complete by December. She said she hopes the messy work of Meier and Stonebreaker will pay off for local officials, taxpayers, and biologists.

“People want to know where their tax dollars are going. They should know that roadways and structures like culverts are being maintained, because if they aren’t culverts can fail. And if there’s flooding from something like that, it will significantly impact people’s homes and businesses. We want to make sure we have the capacity in our waterways to accommodate things like increased storm activities. Keeping waterways open and as natural as possible will help aquatic species make full use of the habitat, but also help humans cope with increasingly powerful storms.”