The Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR) is continuing to enhance and restore oyster reefs on the Peach State’s coast, most recently in a public shellfish harvest area in Glynn County.

Contractors working for DNR’s Coastal Resources Division (CRD) in June placed approximately 140 tons of loose oyster shell in Jointer Creek, west of Jekyll Island. This brings the total oyster shell put back into Georgia’s estuaries in the last 14 months to 213 tons.

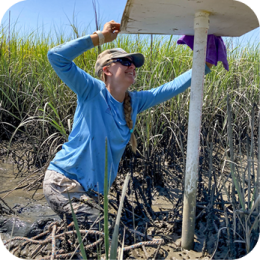

“Oysters, in particular, are very important, as they are ecosystem engineers providing vital services in addition to being a harvest species,” said Cameron Brinton, a marine biologist with CRD. “Oysters help stabilize banks, improve water quality and create essential fish habitat for commercially and recreationally important fish.”

CRD’s Habitat and Artificial Reef program receives significant support from everyday Georgians, as well, Brinton said. That support comes in the form of volunteers who help bag oyster shells for deployment, the donation of oyster shells from area restaurants and funds from nonprofit organizations.

Over the past several months, CRD has focused on three specific projects in Glynn County: a new artificial reef on the Back River near the Torras Causeway containing 68 tons of oyster shell in 7,200 bags; 140 tons of loose shell on the Glynn County public shellfish harvest area on Jointer Creek; and five tons of loose shell in the South Brunswick River near Blythe Island Regional Park.

“The goal of this year’s projects was not only to create new reefs, but also to test new deployment methods,” said Brinton. “In the Back River, we’ve been using bagged oyster shell, which is a method that we’ve successfully used in a number of sites, and at Jointer Creek and Blythe Island, we used loose shell, which requires less manpower and has been very successfully used in other states.”

Although to date the Blythe Island site has only five tons, marine biologists from CRD will return to the site and see how effective the deployment of loose shell was. If the reef is stable, CRD plans to add more shell in the future.

All the oyster deployment sites will be monitored for the next several years looking at several biological and physical metrics to ensure the reefs are stable and self-sustaining.

“The first thing we look for is the settlement of juvenile, wild oysters, called ‘spat,’ which attach themselves to the shell we’re deployment and are the first sign that the reef is starting to grow,” said Brinton. “Later, we measure the size and population density of the adult oysters, and seasonally, we conduct aerial surveys to measure the footprint of the reef.”

A healthy reef should have a footprint that does not shrink. In established reefs, this is not usually a problem, Brinton said, but can be a challenge in newly established reefs due to sedimentation caused by Georgia’s eight-foot tidal cycle.

“With over 3,400 miles of tidal creeks and rivers in Georgia, we have a lot of work ahead of us,” Brinton said. “If you want to help us out, support restaurants that partner with us for shell recycling, donate the shell from your own oyster roast, and consider getting a Marine Habitat Conservation license plate for your vehicle or trailer.”

For more information about artificial reefs in Georgia, visit CoastalGaDNR.org.