Cameron Brinton deals with some heavy stuff in his job -- literally.

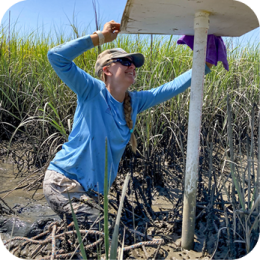

As a marine biologist with the Habitat Enhancement and Restoration Unit of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources' Coastal Resources Division, he helps with the upkeep and creation of artificial reefs off Georgia's coast. Part of his job is to find post-industrial materials like concrete culverts and massive pieces of metal that can be used for fish habitats.

"My job is to maintain, enhance and monitor offshore and inshore reefs and oyster habitat restoration," Brinton said recently.

Those are oyster habitats that are designed for ecological benefit, as opposed to human consumption.

It's a tricky job that requires him to wear a lot of hats, he said. Some days, he's in his office at DNR's regional headquarters in Brunswick, and other days, he's miles offshore. His dutes include sinking barges, putting out bags of oyster shells to encourage fish habitats and catching fish for samples.

"I do a lot of work coordinating with contractors in the build up to the creation of a new reef site," he said. "I'm trying to find materials, manpower -- things like that -- for reefs. All of it leads up to these big bursts where we go out and do the projects. Coordinating all the moving pieces takes weeks, but the actual creation or maintenance of the reefs usually takes two or three days out on the water with all the monitoring and assessing we do."

Brinton also returns to the reefs to check up on them periodically.

"We use technology like side-scanning sonar for offshore reefs and aerial photography on inshore projects to monitor the stability or growth that might be happening on those reefs."

Outside the barrier islands of coastal Georgia, the continential shelf slopes gradually eastward for more than 80 miles before reaching the Gulf Stream. This broad, shallow shelf consists largely of dynamic sand-shell expanses that don't provide the firm foundation needed to develop reef communities, which can include popular gamefish like grouper, snapper, sea bass and amberjack.

That's why CRD has created more than 30 artificial reefs sites offshore, each of which are about two square miles and have several reef piles inside. In all, there are 439 individual, manmade reef piles off Georgia's coast. Most sites are between 6 and 23 nautical miles from Georgia's coast and vary in depths of between 30 and 75 feet.

Georgia's natural reefs occur near underwater rock outcrops and the biological community that establishes itself on manmade reefs is very similar to those that found naturally. These reefs are ideal for offshore fishing because they attract a wide variety of sportfish, Brinton said.

It's not just what's under the water that interests Brinton, though. He's one of a few certified unmanned aerial vehicle pilots at CRD and lends his expertise to other units when needed.

"I was a UAV hobbiest for a while," said Brinton, who lives in Townsend with his wife Brigette. "That gave me a head start on the flight dexterity and being familiar with how UAVs operate. The hardest part was learning all the FAA regulations -- making sure we're flying safely and not interfering with manned aircraft."

In his free time, Brinton enjoys hunting, fishing and PC gaming, he said, which may have helped with his UAV piloting skills. He said he hopes all the skills he's brought to CRD will help keep Georgia's coast beautiful and productive for generations to come.

"One of our main objectives at CRD is to conserve the natural resources and enhance them so that they're maintained and improved for future generations," he said. "I work with a lot of people who are on board with this, and are really excited about the project we're doing to enhance fisheries, create new habitats and restore degraded ones. It's the community involvement that really brings it to the next level, because we can't do this alone."