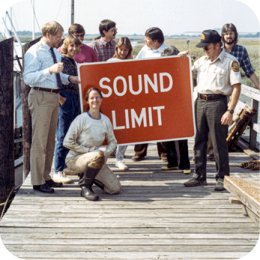

Jim Music, far right, helps pull in a gillnet with the late Capt. Pard Andrew (far left), and marine biologist Bobby Palmer as part of a total estuarine species inventory survey circa 1971. File photo/CRD.

Although he retired from Coastal Resources Division in 2002, former marine biologist Jim Music still keeps a keen eye on what’s happening in Coastal Georgia. As part of our ongoing Retiree Spotlight segment, Coastlines asked Music to reflect on his achievements and how they continue to impact the coast today.

Coastlines Magazine: After spending a career working with Georgia’s marine life, what were the greatest changes that stand out in your memory?

Jim Music: A couple of things: The Coastal Marshland Protection Act has done a lot of good in habitat protection, preventing habitat losses from channelization, filling wetlands, and prevention of hazardous effluents into coastal waters.

• There were basically no recreational creel and/or size limits from when I grew up until after I came to work with the then Game and Fish Commission in July 1970. Most regulatory measures came about after the 1970s. In the early 1980s, we studied recreational fish life histories and made recommendations to protect the spawning populations and enhance the yields-per-recruit through creel and size limits.

• My work in the Commercial Fisheries Section provided baseline documentation of the 1977 winter shrimp kill, and ultimately resulted in then-President Jimmy Carter declaring a Shrimp Disaster Declaration to provide relief to the entire shrimping industry. We closed the fishery that entire spawning season to maximize spawning potential. Today, there is a cooperative Shrimp Fishery Management Plan for the South Atlantic states.

• An overall shrinking of the commercial shrimp fleet was a direct result of the subsequent closing of the sounds following the shrimp disaster. That closure basically eliminated the “Mosquito fleet” (small boats less than 30 feet).

• At one time there were 1,200 licensed trawlers coast wide, with a local fleet in Brunswick docking from the old Brunswick Marine site at Bay and Dartmouth streets down to and beyond K Street. There were also several small scale packing houses, a railway, and a processing plant at the end of Monck and Bay streets.

• New regulatory impacts to the fleet included requirements for TEDs (Turtle Excluder Devices) and BRDs (Bycatch Reduction Devices) in trawls greater than 16 feet, as well. Financial impacts included the influx of imports from other countries, which undercut domestic prices, and, of course, the costs of fuel and insurance if they could get it.

• At that time we also began the sea turtle stranding network to monitor annual mortalities through beach strandings.

CL: What’s the most interesting or unexpected marine life you encountered during your career? (Co-workers don’t count!)

JM: A couple of standouts: An albino blue crab, an albino blacktip shark, the documentation of an hermaphroditic spotted sea trout, and the fall/winter migration of Right whales during our off shore sampling.

CL: What conservation efforts are you most proud of being a part of during your time with the CRD?

JM: The recreational fish life history study that John Pafford and I did in the 1980s that helped in the efforts to regulate creel and size limits for that fishery; Drafting regulations for the Board of Natural Resources, including recommendations for limiting the number of crab license holders and the subsequent number of traps per crabber; Implementing gear restrictions, e.g. BRDs and TEDs; Drafting castnetting regulations; and my participation in the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission developing fishery management plans; and coordinating with other state fishery managers—Sea Map studies, technical committees, and creating Fishery Management Plans.

My last state regulatory task was developing the “mud minnow” (mummichog) regulations for commercial and recreational limits, gear descriptions and numbers, and quantity limits. This required preparation of experimental contracts, drafting rules and regulations, and conducting public hearings.

CL: What do you see as the biggest challenges facing Georgia’s marine environment in the coming years?

JM: Maintaining Habitat Protection—The coastal population explosion and desire to build private and commercial developments on or near coastal waters is a never-ending pressure. We must not allow dilution of the current protections.

CL: Do you have any recommendations for how everyday citizens can help protect Georgia’s marine life?

JM: We are all stewards of our environment. Everybody needs to be aware that every little piece of discarded debris and effluent into the ecosystem has an adverse impact—much the same as the straws which break the camel’s back.

CL: Having explored the Georgia coast extensively, can you share a favorite hidden place or underwater location?

JM: Two places come to mind. First, Egg Island for recreational fishing for food fish, and St. Andrew Sound near Little Cumberland Island for heavy duty shark fishing for fun fishing.

CL: For someone interested in a career in marine biology, what advice would you give them?

JM: A Master’s degree in marine science, preferably fisheries specific science. Computer skills and statistical skills are also very important. It’s difficult today to initially get your foot in the door with a Bachelor’s degree.

CL: Can you describe a particularly memorable or challenging DNR project you participated in?

JM: I’m proud of our recreational fishery work of the 1980s, and it was the most fun for all of us who participated in that work.

CL: Since your retirement, are there any specific ways you stay connected to the marine world?

JM: I retired in January 2002, and I still enjoy visiting the staff when I update licenses and such. However, I did help Carolyn Belcher (current CRD Chief of Fisheries) with her shark tagging study, and I also helped collect samples for the LCP Superfund Site study to be used to set seafood consumption guidelines for Georgia waters.

Initially, I tried charter fishing and wanted to work two or three days per week, but I soon realized that it took up two additional days for preparations and clean up, so I settled on my current job as a role player at the Federal Law Enforcement Center (FLETC). I have been there since 2003, and I think I’ve found my niche.

CL: Is there a little-known fact about Georgia’s marine life that most people wouldn’t know?

JM: Many marine species are strongly habitat specific. Example: There are locally three common species of fiddler crabs and each have specific substrate and salinity preferences. Notice where you’ll find them when you walk in and/or along the muddy marsh versus the sandy areas or salty versus brackish areas. Thus, the entire ecosystem needs our protection.